‘Facts, Sir, Are Nothing Without Their Nuance.’

So said Norman Mailer, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author, testifying in the controversial trial of seven Americans arrested for protesting the Vietnam War (the “Chicago-7”), one of the United States most celebrated free-speech cases. To help us navigate the fraught path of delivering meaning from impartial information, we’ve created this Intermediary Liability Blog.

Disinformation and COVID-19: Two Steps Forward, One Step Back

Few issues have brought the challenge of Internet regulation to the fore more than the recent COVID-19 crisis.

The global pandemic and ensuing lockdown offered a near-perfect petri dish for testing the commitment of platforms to the spread of correct, accurate health information under the most trying, jarring circumstances – and for making sure that evil doers weren’t able to deflect blame from themselves and sew mistrust in public institutions at a crucial, delicate moment.

False information that could harm the health of users is banned on most platforms; community guidelines mandate clearly that harmful and misleading user-generated health information is content whose spread they should block and whose lies they should remove. So there’s no question about the platforms having or not having a mandate here. The issue is, how seriously do they take it? And how effective are the policies they enact at stopping the spread of harmful disinformation?

The answer seems to be two-fold. As the COVID-19 virus spread, the platforms showed themselves ready to take unprecedented steps to attack the problem, including (in the case of Facebook) putting correct, public-health-authority-approved advisories and information at the top of every global news feed across their two billion-person network. But the unprecedented effort also revealed how serious the problem is – and how easy it is to take advantage of the usual hands-off approach. Put simply, harmful disinformation continued to spread – though it did so in much lower volumes than would have happened had it not been contained as a matter of official policy.

Early in the crisis, platforms found they were fighting a complicated war on multiple fronts. Not the least of their problems were state-funded disinformation campaigns and the state actors behind them: The Chinese government, for one, was working overtime to spread lies and re-position itself as a helpful foreign ally despite having contributed mightily to the virus’ initial outbreak and spread. In an effort to reassure an increasingly nervous public, U.S. President Donald Trump suggested people might be able to cure the virus by ingesting bleach.

Harder to stop were private citizens, some of whom make careers by promoting conspiracy theories and drawing attention that way. Their motivation is hard to ascertain. It could be profit; it could be something else. But either way their actions are deeply harmful. Even more nefarious is the perilous combination of the two: conspiracy theorists whose voices are somehow amplified by state-run media campaigns and foreign-operated bots. Put simply, the disinformation campaigns on COVID-19 evolved like a virus, mutating in response to efforts to extinguish it. Platforms have, for example, taken down many fake accounts in recent years; but governments with active disinformation programmes have learned they can avoid fake-news filters by waiting for domestic purveyors of disinformation to post content – then using their bots to spread those lies.

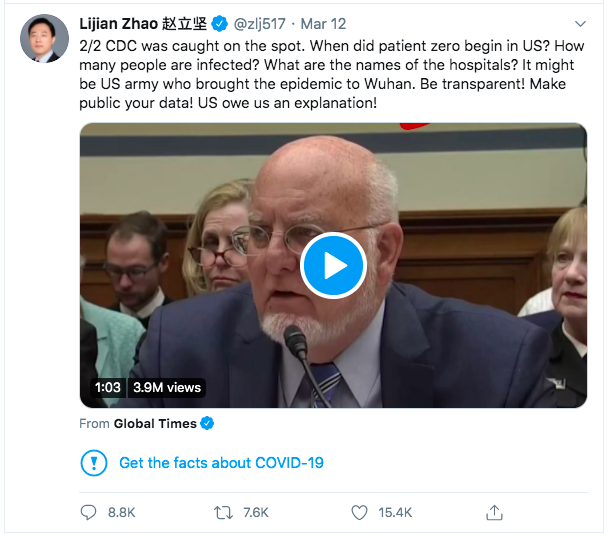

One way of dealing with the problem was to make sure people got good, accurate information not from conspiracy theorists or twisted government propaganda but from reliable public health authorities. And that’s what Facebook did; official health information on stopping the spread of coronavirus now appears at the top of every Facebook news feed, worldwide. Twitter, too, took unprecedented steps, providing alternative sources of information alongside factually incorrect tweets from U.S. President Trump and Chinese Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Lijian Zhao.

How effective has this effort been? A study in April 2020 from the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism (working with the Oxford Internet Institute and the Oxford Martin School), found that, while the number of fact checks of English-language online content soared 900% in January-March 2020, 59% of the posts rated as “false” by independent checkers could still be found online at the end of the period; YouTube and Facebook did somewhat better; only 27% and 26%, respectively, of posts rated “false” remained up. The study also found that disinformation from official government sources had an unusually large impact; state-backed media – including government-run “news” outlets in China, Iran, Russia and Turkey – produce relatively little content but have massive “engagement” with English-speaking audiences around the world – roughly 10 times more than the BBC. The Reuters Institute calculates that official disinformation constitutes only about 20% of the disinformation circulating online, but it gets more than two-thirds of all social-media engagement.

The Reuters Institute summarises the themes and between-the-lines messages emerging from these government-backed campaigns: 1) criticism of democratic governments as corrupt and incompetent, 2) praise for their own country’s global leadership in medical research and aid distribution, and 3) promotion of conspiracy theories about the origins of coronavirus.

Perhaps the best illustration of how – and why – this phenomenon is so hard to regulate on platforms that insist on remaining open is the case of Plandemic, a 26-minute film produced with the input of a discredited anti-vaccination campaigner. The film – which alleges that a shadowy cabal of global elites are profiting from the spread of coronavirus and the coming effort to vaccinate against it – has been removed from all mainstream social-media platforms after being fact-checked as false and misleading. But not before it was viewed eight million times, shared 2.5 million times in a three-day window and spread well beyond the Facebook, YouTube, Twitter and Instagram sites where it was initially uploaded (QAnon, a 25,000 member group that pushes rightwing conspiracy theories, played a crucial role in its early spread). A New York Times investigation shows how the audience started small, but, relying on a re-post from a popular television “doctor” (with 500,000 Facebook followers) and a mixed-martial arts fighter (with 70,000 Facebook followers), it went viral and soon broke into the mainstream U.S. political debate. The debunked film eventually made its way to the website of Reopen Alabama, a 36,000-member group pushing for the U.S. state to end the lockdown despite health guidelines. In the end, the momentum that digital technology gives conspiracy-driven communities like the ones behind Plandemic could be slowed but proved difficult to stop.

The more important news may not be that truth filters don’t always work or that the system can still be gamed. Much more significant is the new approach emerging over disinformation; as of 12 May, more than 50 million pieces of misleading health-related content had been flagged and given warning labels on Facebook alone; simultaneously, Facebook reported more than 350 million click throughs to correct and accurate information on the pandemic’s spread and the safety measures expected of the population.

Regulators and platforms showed that – in a public emergency – they can work together to get reliable information out to people. And some platforms also showed that, when it comes to public health, they are not prepared to let political leaders abuse their platform to spread disinformation – even when it means facing the full wrath of those leaders for calling “malarkey” over their lies. These are important precedents, going forward. A new atmosphere has been created, a new spirit of public-private collaboration for more socially responsible outcomes and – perhaps most importantly – a re-dedication to science and evidence within the bellies of the platforms where so much social interaction now takes place. It’s up to us all to demand only the best of our companies and public institutions, to consolidate these gains and to make sure the Internet remains a tool for spreading democracy – and not for destroying it.

PAUL HOFHEINZ

Paul Hofheinz is president and co-founder of the Lisbon Council.

More Analysis

A Critique of Pure Friction: Does More Hassle Mean Additional Safety and Better Regulation?

Context is King: How Correct Data Can Lead to False Conclusions

Fighting Counterfeits or Counterfeiting Policy? A European Dilemma

Donald Trump, Sedition and Social Media: Will the Ban Stop the Rot?

Country of Origin: New Rules, New Requirements

Illegal Content: Safe Harbours, Safe Families

Regulation and Consumer Behaviour: Lessons from HADOPI

Incitement to Terrorism:Are Tougher Measures Needed?

Creative Works, Copyright and Innovation: What the Evidence Tells Us

Online Hate Speech: Does Self-Regulation Work?

Disinformation: How We Encounter, Recognise and Interact with It